On this page

-

Text (2)

-

Untitled

Untitled -

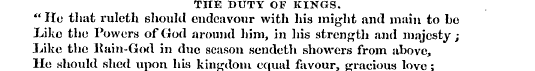

TnE DUTY OF KINGS. " He that ruleth shou...

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

-

-

Transcript

-

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

Additionally, when viewing full transcripts, extracted text may not be in the same order as the original document.

Only Erroneous But Move In A Path Whereo...

as a Daw , he will do for Morals what Newton _did'for Physics ; and not till then . . , The misconception of the nature of Daw which pervades this work , is accompanied hy as greater misconcep tion of the scientific nature of Analogy , so much emp loyed b y him , e . g . —~ religion and electricity . " In this connexion between violence and religious feeling , there are not wanting analogies with material phenomena . If the divine and spiritual principle of sincere religion has occasionally produced fruit so strange and unexpected as hostility and bloodshed , persecution and hatred , so bave the subtler material elementshowever pervading may be their salutary effects—produced accompanying evils , which can neither be evaded nor denied . One of the subtlest of our atmospheric elements is electricity . Of the great part it plays in promoting vegetation , in the formation of rain and dew , and in the regulation of climate and temperature , there can be little doubt . Yet it is probable that this recondite but salutary and beneficent agent is , in its changes and mutations , one of the causes of those mysterious visitations of pestilence and famine that , from time to time , in all recorded ages ,

have , at certain periods , afflicted the world . The same may probably be true of magnetism and of galvanism , if these be not indeed modifications only of electricity . Thus , then , in both worlds , material and moral , evils may accompany , and do accompany , the most refined and spiritualised , as well as the grossest and most tangible agencies . Electricity becomes the source of disease and death ; religious zeal , of persecution , cruelty , and aggression . The best of motives and agents are not good unmixed , as the worst are not altogether bad ; and as that electric fluid , which is present in the rain and dew that refreshes all nature , is the moving power likewise in the thunderstorm , the tornado , the pompero , and tbe hurricanebreathes pestilence in the sirocco , and storm in the monsoon—so have the mild teachings even of Christianity their possible tendencies to an opposite influence , and from the Sermon on the Mount the perversity of human passion has elaborated a Sicilian Vespers and a Saint Bartholomew !"

Monmouth and Macedon both have M . as their initial . This work is , however , only one of a class . So long as men attempt the scientific solution of moral problems , and neglect the Method of positive science , so long will they wander helplessly through the labyrinth without a clue .

Ar01803

Tne Duty Of Kings. " He That Ruleth Shou...

TnE DUTY OF KINGS . " He that ruleth should endeavour with his might and main to be _JLiko the Powers of God around him , in his strength and majesty ; Like the Rain-God in due season sendeth showers from above , He should shed upon his kingdom equal favour , gracious love ; As the Sun draws up the water with his fiery rays of might , Thus let him from his own kingdom claim his revenue and right ; As the mighty Wind unhinder d _bloiveth freely where he will , Let the monarch , ever present with his spies all places fill ; Like as in the judgment Yama punisheth both friends and foes , Let him judge and punish duly rebels Who his might oppose : As the Moon ' s unclouded rising bringeth peace and calm delight , Let his gracious presence ever gladden all his people ' s sight ; Let tbe king consume the wicked—burn the guilty in his ire , Pright in glory , fierce in anger , like the mighty God of Fire ; As the General Mother feedeth all to whom she giveth birth , Let the king support his subjects , like the kindly-fostering Earth . " But , the most beautiful of all is that " Death of the Hermit Boy" from tho " Uamayana . " The bereaved king , wIioho son has just been taken from him , recurs in his sorrow to an early crime , and sec in his present allliction a punishment : — " Spake he sorrowing to Iv . _vnsnlya , sighing , weeping , for her son : — ' Art thou waking , mournful lady ? give me all thy listening ear , Hearken to a talc of sorrow , —to an ancient deed of fear . Surely each must reap the harvest of his actions here below , Virtuous deed shall bear a blessing , sin shall ever bring forth woe ; I . right are tho I'ahisa ' _s blossoms , homely is the Amru tree , And a man will fell the Amras , tend _l'alasas carefully . For awhile his heart is merry , when he sees the flowers ho fair , But in summer-time he sorrows , seeking fruit , for none is there . Fool ! 1 wafer'd bright I _' _tihums , laid the useful A turns low ; Now I mourn for _hanish'd Kama , and my folly finite th woe . 'Tis a deed of youthful rashness brings on me this evil day , As a young child tnsteth poison , eating death in heedless play . ' *' He relates how he waited in ambush to try his archer-skill , and fancying ho heard a wild beast" lOagcr to lay low the monster , forth a glittering shaft 1 drew , 1 _'oixonouH as fell serpent ' s venom from the string the arrow How ; Then 1 heard a bitter wailing , and a voice , ' Ah , me ! ah , mo !' Of one wounded , falling , dying , calling out in agony ;

SPECIMENS OF INDIAN POETRY Specimens of Old Indian Poetry . Translated from the original Sanskrit into English Verse . By Ralph T . H . Griffith . Arthur Hall , Virtue , and Co . Those who complain of the neglect of the Indian Muse , forget that beyond the remoteness of Indian thought there lies another cause—inadequacy of translation . Few poems read well in translation , and none where the substance is not of itself interesting enough to dispense with form . Now in Oriental poetry the form is everything ; and that form is so opposed to all our ideas , that in translation it is apt to be wearisome bombast . Translation is always a makeshift . But as English readers are not likel y to learn Sanskrit for the literary deli ght of enjoying Indian poetry , one is very glad to get hold of a makeshift , that some dim image may be seen , " as in a glass darkly , " of this Indian Mnse . Hence the interest of such a work as Mr . Griffith ' s . It is an unpretending little volume , but lovers of literature will prize it ; and as our own poets are silent just now , a hearing may be gained for these voices of an earl y world . The " Veda Hymns" with which the volume opens belong to the _untranslateable class . The extracts from the " Book of the Daw of Manu , " the " Ilamayana , " and the " Mahabharata" are more intelligible . Erom the first Ave extract

Tne Duty Of Kings. " He That Ruleth Shou...

Writhing on the bank in anguish with a plaintive voice cried he « Ah ! wherefore has this arrow smitten a poor harmless Devotee ? Here at eve to fill my pitcher to this lonel y stream I came , Tell me , whom have I offended , how have I deserved blame ? Who should slay the guiltless Hermit , living in the secret wood , His sole drink the river water , simple herbs and fruit his food ? Will the murderer spoil my body ? Am I for my vesture slain ? Little from my deerskin mantle , or my bark coat will he gain ; 'Tis not mine own death that pains me—from my aged parents torn , Long their stay and only succour— 'tis for their sad fate I mourn . Who will feed them when I am not ? Heedless youth , whoe ' er thou art Thou hast murder'd father , mother , offspring—all with one fell dart . ' ' Horror seized my soul within me , and my mind was well-nigh gone , In the stilly calm of evening as I heard that piteous moan ; Rushing forward through the bushes , on Surayu ' _s bank I spied ,

Lying low , a young Ascetic , with my shaft deep in his side ; With his matted hair dishevell'd , and his pitcher cast away , From his side the life-blood ebbing , smear'd with dust and gore he lay ; Then he _fix'd his eyes upon me , —scarcely could my senses brook , As these bitter words be utter'd , that long last departing look : — ' Only to fetch water came I—tell me , wherefore do I bleed ? Have I sinn'd against thee , monarch ; done thee wrong in word or deed ? Ah ! I ' m not thine only victim—cruel king , thy heedless dart Pierces too a father ' s bosom , and an aged mother ' s heart . They , my parents , blind and feeble , from this hand alone can drink , When I come not , thirsting , hoping , sadly to the grave they'll sink . No fruit from my Veda studies , none from Penance do I gain , Por my hapless father knows not his dear son is lying slain ; Ah ! and if he knew me dying , powerless to save were he , As a tree can never rescue from the axe the doomed tree .

Hasten to him , son of Raghu ! tell my father of my fate , Lest his wrath like fire consume thee—hasten ere it be too late I There within the shady forest is my father ' s hermitage , Go , entreat him , son of Raghu ! lest he curse thee in his rage ; Hasten , king !—but first in mercy draw this arrow from my side j Ah ! it eats away my body , as the river-bank the tide . ' Mind-distracted thus I ponder'd ; —Now he writhes in agony , When I draw the deadly arrow from his body he must die , Quick he saw the doubt that held me , pitying , fearing , where I stood , And the wounded boy address'd me , conquering pain by fortitude : — ' Let not thy Bad heart be troubled for thy sin if I should die , Lessen'd be thy grief and terror , for no Twice-born , King ! ami ; Fear not , thou mayst do my bidding guiltless of a Brahman ' s death , Wedded to a Vaisya father , Sudra mother gave me breath /

Thus he spake , and I down kneeling , drew the arrow from his side j Then the Hermit , rich in penance , fix'd his eyes on me , and died . Pierced through , wetted by the ripples , by Surayu lying dead , Bitterly I _mourn'd the Hermit , weeping , much disquieted . Motionless I stood in sorrow—sadly , anxiously I thought , How to minister most kindly to the woe my hand had . wrought . From the stream I fill'd the pitcher , and , as he had told the road , Quickly reach'd the lowly cottage where the childless twain abode ; Talking of their son ' s long tarrying , a poor aged sightless pair , Like two birds with clipt wings , helpless , none to guide them , sat thoy there Sadly , slowly , I approached them , by my rash deed left forlorn , _Crush'd with terror was my spirit , and my mind with anguish . torn ; At the sound of coming footsteps thus I heard the old man say , ' Dear son , bring me water quickly—thou hast been too long away ! Bathing in the stream , or playing , thou hast stay'd so long from home ; Come , thy mother longeth for thee—come in , quickly , dear child , come , Be not angry , mine own darling—keep not in thy memory Any hard word from thy mother , any hasty speech from me ; Thou art thy poor parents' succour , eyes art thou unto the blind ; Speak , on thee our lives are resting—why so silent and unkind ?' Thus I heard , yet deeper grieving , and in fresh augmented woe , Spake to the bereaved father , with words faltering and slow . "

After relating what has befallen" O ' er his cheeks at my sad story _flow'd the tear-streams in a flood , Scarce for weeping spake tho hermit , as with folded hands I stood ; ' King ! hadst thou conceal'd this horror—this blood-shedding left untold , On thy head thc sin had fallen with its fruit ten thousand-fold ; For a Warrior stuin'd with murder , of a Hermit above all , From his high estate , blood-guilty , were he Indra ' s self , must fall ; Thou dost live , for all unconscious , monarch ! didst thou slay my son ; Else had all the race of Raghu fallen , by thy deed undone ; Lead us , king , by thee bereaved , lead us to tho fatal place , Let us fold our darling ' s body in a long and last embrace / By the hand I led tho mourners to tho river where he lay , Fondly clasp'd the sightless parents in their arms the death-cold clay-* We omit tho lamentations of tho father , followed by the funeral preparations—tho poem thus concludes -. — " Duly were the sad rites ended by thc parents' loving care , And again the Sage address'd me as I stood a suppliant there : — 'Thou bast slain my well-beloved , —robb'd my one dear child of breath , Slay ine , slay the childless father—there is now no sting in death . Hut—for thou hast kill'd my darling- wretched King ! thy breast shall _kno Something of tho pangs 1 tndfer a bereaved father h woe . —¦ Thus I lay my curse upon thee—for this thing that thou hast done , As I mourn for my beloved , thou shall , sorrow for a son / Thus the childless Hermit cursed me , and straightway the nged p »» r To the funeral pile ascended , and breathed out their spirits there . Lndy dear ! that youthful folly fruiteth woo upon my head , Heavy ' n my heart , within me , nnd my soul disquieted ; Yen , the ancient Hermit ' s cursing is _fulfiU'd <> n me this day , — Sorrow for iny hanish'd Rama taketh all my life away . Kiss me now , my own _Knusalya , quickly will my vital breath Leave me at the awful summons of tho messengers of Death ;

-

-

Citation

-

Leader (1850-1860), Aug. 28, 1852, page 18, in the Nineteenth-Century Serials Edition (2008; 2018) ncse-os.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/periodicals/l/issues/cld_28081852/page/18/

-