On this page

-

Text (2)

-

![Un 24. 1852.] ®%t %9H*tt. . ™](/static/media/periodicals/101-CLD-1852-01-24-001-SINGLE/Ar01102S.png)

Un 24. 1852.] ®%t %9H*tt. . ™

-

address of tbpebtoob-t-a ^ Association t...

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

-

-

Transcript

-

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

Additionally, when viewing full transcripts, extracted text may not be in the same order as the original document.

The Amazon. Nothing Material Or Novel Ha...

r—^ fth at thev came from the stewardess . adkne «? SoiwS saw no signs of flames , but he hastened Tthe 8 Ss on tcvt ^ e deck . He there saw no crowd of up * JSt . erson to give an alarm ; but he saw amid-P P « the raefngofthe ^ ames towards Heaven . He then a T ^ S 8 £ t * wi lowered at the side of the ship , and Koti 4 Se bulwarks with a view of letting himself Sriwn into it ; butiii consequence of his ^ roken leg he was -JLftStoi to let himself down , intending to swing hlmt $ &\ tebZ £ *& c * me under him . At that moment the ? S ga ? l way / and the boat was swamped-and he saw those whom it had contained struggling m the water with Kh Two or three were still on the upper part of the S and he appeared to hear a voice whisper to him , ? HoidTon , and aU will be right . ' Having mounted the vpssei he lowered himself into another boat , about Lenty-five feet above the water , so great and lofty was Tnat siuck naicnes

that noble vessel . Doac on me , auu they could not get it off rbat suddenly . the boat was capsized , and how he kept his place in thehoat he could not recollect , but he began to imagine . the horrors of death by drowning . Suddenly the boat righted , and she was swung , with thirteen people in her , from the ship , but the tackle could not be disengaged from her . A sailor called for a Knife , to cut the rope—the rope was cut , the ship was gone , and they were left to the buffettuiR of the waves : and here he felt bound to praise that God

who controlled all things , and held the mighty deep m the hollow of His hands , for his preservation . When the boat got clear of the vessel , it was discovered that she had got a large hole in the bottom , and it was feared she must sink . One poor man placed his arm into the hole , and asked for something to plug it with : one gave his hat , another his drawers , another his stockings and other things ; and that the watchful eye of God was still over them , was shown by the fact that two small vessels had been left on board the boat , which served them to bale out the water and keep her from swamping . "

A portion of the paddle-box and some of the machinery of a large new steamer have been Washed on shore at Bridport , and is supposed to be a part of the ill-fated Amazon . Information has already been forwarded to the Admiralty , and the officers of her Majesty ' s Customs have taken active , measures for securing the portion of the wreck , which is of Borne value oft account of the quantity of coppdr and brass attached to it . ., - . < ¦ ¦ . The sufferers haye ; beerj ^ generously cared for at Plymouth and Southampton . ^ .

Un 24. 1852.] ®%T %9h*Tt. . ™

Un 24 . 1852 . ] ® % t % 9 H * tt . . ™

Address Of Tbpebtoob-T-A ^ Association T...

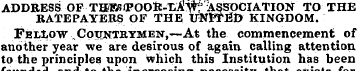

address of tbpebtoob-t-a ^ Association the RATEPAYERS OF THE UNl-Tfifc KINGDOM . Fellow , Countrymen , — -A-t the commencement of another year we are desirous of again calling attention to the principles upon Which this Institution has been founded , and to the increasing necessity that exists for their adoption and enforcement by the Legislature . Our object is—To abate the evils of pauperism , and to reduce poor rates . Our means are—The substitution of reproductive employment of the poor , either upon the land , or in handicraft labour , instead of the odious and repulsive labour tests and relief system ; and thus to render the poor-law establishments nearly or altogether self-supporting .

In a word , the aim we have in view , and which we confidently call upon the country to assist us in achieving is , to benefit the ratepayer by benefiting the poor . The burden of poor rates has increased in density year after year ; and whithersoever we turn we discover no prospect of improvement , save in the adoption of the principles of this Association , The evil is getting worse and worse , At first it was , so to speak , like " a cloud no bigger than a man ' s hand ; " now it is like a flight of locusts , threatening to eat up every green thing . In many districts in Ireland numerous rentals have been entirely swallowed up by the poor rate . Take the following statistics , illustrative of the tremendous increase of this impost in the sister kingdom : — In 1840 the expenditure for administration of Irish poor law , was £ 37 , 051 1841 Ditto do . 110 , 278 1842 Ditto do . 281 , 233 1843 Ditto do . 244 , 374 1844 Ditto do . 271 , 334 1845 Ditto do . 316 , 225 1846 Ditto do . 435 , 001 1847 Year of famine , do . 803 , 084 1848 Ditto do . 1 , 826 634 1849 Year of cholera do . 2 , 177 , 651 The expenditure for the year 1850 fell to £ 1 , 430 , 108 , a lact which is no Bubject for gratulation , as , alas ! it is mainly attributable to the frightful diminution of the P » ' P ° iaHy by death , as the last Census returns ao faithfully testify . The above figures require no commentary to sustain th ! :. i e j eM »« 5 ntly than words do they proclaim the ut er inadequacy of the law to accomplish the object thlT n lt ** 8 avowedlv fra" > ° d . It will be seen that ™ i ?« * u 8 exaoti ° n was multiplied in tho very years when the country was lea ^ t able to meet it-when lying prostrate under the successive visitations of famine and 8 te 1 In annum

tlWnrSl ^^ ? ? '» P ^ wrung from thJK f " « InduBtrial resources of Ireland , for lStC'ir ^ th ^ niJ ? ! ** Canthe Statesman , the ' Phi-SriWbeon ClSr 0 hri 8 ^» » « a « sfy himeelf that the poor tfft Fffi 3 iJli h " f ? 2 , May we not Ouoto tho worda tim « i i B applied to theoonditionof * Englftndmhifl to refl 7 rtt liXT ° f tter e t ° ni 8 hihent to any m " n to refltot that , in a country where the boor arc bevond a comparison , more liberally provided for than hJw ^ SaB £ S 5 » s «« 3 unaer the Irish , poor-law administration ,

notwitUstanding the enormous supplies levied by it , thousands and tens of thousands of our fellow-creatures have notoriously died of starvation . Under that system , notwithstanding that the workhousea are full , the country , is ravaged by hordes of mendicants , who , like guerilla bands , prowl from village to village , extortingirora the unfortunate taxpayers 'the remnant that has been left them by the poor-rate collector—for * ' what the eaterpillar has spared , the cankerworm has devoured . " Under that systemj cargoes of Irish paupers have been thrown upon the coasts of England and Scotland to swell , to an intolerable extent , the ranks of pauperism in London , Livernbol . Manchester , Bristol , Glasgow , & c , & c .

Under that system , humanity has been degraded below the level of the brute creation ; and in Irish board-rooms and English vestries the price of sending 80 many paupers to Liverpool , or despatching them back to their native parishes , has been debated with infinitely greater callousness than would be exhibited in a discussion between a Smithfield crazier and a shipping agent , on the subject of the transmission of so many head of horned cattle . It is impossible to avoid shuddering at a condition of things of which these features are the indices . The social position of Ireland , under the operation of the poor law—a position which menaces a speedy extinction of an entire people—as it cannot be contemplated

without horror , so it cannot be justified by the most subtle sophistry . In that country there are millions of acres of Waste lands , which only require the application of labour , that is now waste , to make them yield their increase , and augment the wealth of the State . Shall we not make an effort to remove this anomaly ? or , to use the language of a respected member of the Legislature , and of this Association , in his letter to Lord Jobn Russell , in 1847 : — " Shall we , my lord , wait for some terrible convulsion , before you appropriate the waste lands of Ireland

*—the peoples' farms—to the use of the people f " The social cancer is also steadily eating its way in England , the charge in 1849 being £ 5 , 792 , 963 . In 1836 , the expenditure for the relief of the poor of Manchester was only £ 25 , 000 , but it reached £ 120 , 000 in 1848 . This annual charge has since been reduced , owing simply to the abundant employment of the working classes in this district . Any one who has watched the mutations in the manufacturing districts , within the last half century , will readily decline the task of deciding how long this : happy employment of the people , and consequent diminished charge for pauperism , may be expected to ¦

last . 1 ' •¦• In a late return to the board , there is a passage pregnant with importance , as illustrative of-the injurious effects upon England of the overflow of Irish pauperism : — " The relief granted during the week ending December 17 , 1851 , in the township of Manchester , was as follows : —Settled poor , 1951 cases , at a cost of £ 231 . 5 s . 5 d . ; Irish , 1780 cases , at a cost of £ 221 . 10 s . 9 d . ; English non-settled , 876 cases , at a cost of £ 108 . 17 s - 2 d . Compared with the corresponding week of the previous year , there was an increase of 188 English cases , and £ 4 . 3 s . 6 d . in the cost ; and an increase of Irish cases , and £ 36 . 2 s . 6 d . in the cost . "

This tax upon the industry and property of the country is becoming too heavy to bo borne longer , without an effort to throw it off or mitigate it . So wretched , indeed , is the method of disposing of the impost , that it is a question whether the poor or the rich are actually more dissatisfied , or have greater reason to be so , Bince the plunder of the one serves so little to the real advantage of the other . And if this evil be not corrected in a time of almost profound peace and comparative prosperity , how will it be endured in a season of commercial or manufacturing distress , when thousands of hands will be thrown of employment , to add to the number of recipients of relief—how tolerated in a currency crisis—or how will the Chancellor of the Exchequer find dividends in any future war , to pay the interest of an increasing debt ?—all possible contingencies , which it becomes the statesman seriously to contemplate and provide against .

The remedy which we suggest for this crying evil—the instruction and employment of the poor in' works of a remunerative character—is not a new panacea . It has had the sanction of some of the most illustrious names in English history and literature ; and it has had the imprimatur of success , wherever it has been judiciously The celebrated statute , the 43 rd d'f Elisabeth—the maladministration , not the principle , of which demanded a change—was drawn up by the great Lord Bacon , and " gave power to raise by assessment , to purchase a stook of wool , hemp , flax , & c , for the employment of the

Lord Halo prepared a scheme , well worthy of hia Lord Halo prepared a scheme , well worthy ot lua highly-gifted intellect , for the employment of the poor in workhouses , which would have been a great improvement upon the 43 rd of Elizabeth , innsmuch as it rendered it compulsory upon the justices of tho peace to procure stock for the poor , when the overseers neglected this duty . One of the suggestions of Lord Hale demonstrates that the sale , outside , of the goods manufactured in the workhouse , was a part of his plan : —" Ihftt there be yearly chosen by the said juatioeo , a master for eaoli workhouse , with a convenient Balary , out of the aald stock , or the produce Jhei ' cof , to continue for three t tiuuciuc »/« — —

! rears , it is accpiy o ua u »« " *•*» »•» .., .--ooked forward to the accomplishment of his scheme for the improvement of tho condition of the poor as tho crowning act of hia public life—as a work of great humanity , " worthy of a Christian and an Englishman — was removed by death before ho had time to press It upon the attention of tho Legislature . Sir Joshua Child , who wrote elaborately on tho subject , gave the following as the reault of his reflections : — " It is no matter whether the manufacture in the worichouse turns to present profit or not , the great business of tho nation being—first , to keep tho poor from begging , and starving , an 4 inuring ouch , as wo able to labour and

discipline , that they ; tnay be hereafter useful members of the kingdom . " In 1697 , Mr . Locke suggested that , ' * houses of industry were the means to increase the quantity of labour throughout the kingdom , and decrease the expense of maintaining the poor /' Against these opinions , emanating from the " master Spirits of the age" in which they lived- —against the light of reason , the testimony of experience , and the dictates of humanity—the disciples of a false version of political economy present us with certain fallacies , which , although they have been often refuted before , it may be necessary here again to notice . First , it is urged that the substitution of employments

of a healthful and remunerative charactive for compulsory idleness or cruel and repulsive task work , such at picking oakum , & c , would interfere with the means of testing cases of real destitution . In answer to this objection , we submit , thatthe test system itself is unjust , and the sooner its doom is sealed the better . The right of the poor to relief on the soil that gave them birth is as sacred , as ancient , as fully recognized by statute and by judicial authorities , since the days of Richard II . downwards , as any right to property , title , or prerogative , possessed by the highest in

the land . This being the case , is it just to clog their acceptance of relief with conditions so revolting that , in thousands of cases , it is notorious they endure the utmost extremity of suffering rather than apply for assistance ? The pauper , living in a highly artificial state of society , finds himself reduced , by circumstances over which , perhaps , he has had no control , to indigence ; and unable longer to support himself , his wife , and children , without extraneous aid , he presents himself to the guardians of the poor , and in obedience to the primseral mandate from on high— " In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread until thou return to the ground "—he

" Humbly asks his fellow-worm To give him leave to toil . " He does not demand subsistence for nothing . The only capital he has in the world is the labour of his hands , and that he is willing to give in return for the assistance advanced to him . He desires " to take his portion , and rejoice in his labour , for this is the gift of God . " But he is stopped at the threshold by the stipulation which is imposed upon him , viz ., that , if he enter the workhouse , he must be content to languish in total idleness , 4 ) t go through a certain amount of task work , which , while it thoroughly disgusts him ^ neither is , nor is intended to be , of any benefit to the public . It is hard to say whether the injustice of this system to the poor , or the absurdity of advocating it for the benefit of the ratepayers , is more transparent . In the case of youthful paupers , the weight of our argument is greatly enhanced .

" Ju 3 t as the twig is bent the Uee's inclined . " Under the plan we recommend , industry would keep the rising generation from mischief , and fashion the future man for a life of honesty and self-dependence . Another objection presented by pseudo-political economists to the carrying on of reproductive labour by guardians is , that it interferes with independent industry . At acursory glance , this objection may appear to possess some force ; but a closer observation will discover that it is wholly untenable . Expounders of political economy should be the last persons to advance this objection , for that science teaches us , " That the wealth and prosperity of a kingdom increase in a ratio with the aggregate of the money earned by the labour and employment of its

inhabitants ; " and " that production generates demand ;" and the highest authority that could be appealed to assures us " that idleness is the root of all evil . " It is asserted that the application of the labour of the inmates of poorhouses to works of a remunerative nature is an injustice to the workmen who are supporting themselves without parochial relief ; and that it is better for the latter that the former should be supported in total idleness . This proposition is as rational as if we said that in a family of six persons three should insist upon doing all the work , and complain that they were about to be plundered , if the remaining three contributed aught towards the common stock ! Three should " eat the bread of idleness . " in order that the labour of the other

three should not be interfered with ! The proposition is aa sensible as if we said that one half of the factory labourers in Manchester should be drafted to the poorhouse , there to receive relief at the cost of the remaining eons and daughters of industry . What Bhould we think of the sanity of a man who , about to walk a considerable distance , insisted that he would advance with greater ease and speed if permitted to carry a neighbour on his back ? Beyond all doubt , if the suffrages of the workmen of this country were taken upon the subject , all of them , who are not blinded by ignorance and prejudice , would unhesitatingly concede to the indigent unemployed the privilege of contributing to their own support by the labour of their hands , and to the consequent reduotion of the burden of poor rates , which preBacs so severely upon all classes , from the landed proprietor and oapitaliet to the hard-working mechanic .

Will tho opponents of the self-supporting system display the temerity of asserting , that the predent administration of the poor law has not most seriously affected Independent industry in Ireland , by swamping the rentrolls of the landlords , driving the farmers out of the country by hundreds of thousands , and pressing bo heavily upon the trading classes in the towns as to compel thousands of onoe comfortable ratepayers to become recipients of in-door relief ? Has it not seriously interfered with the labour markets of England and Scotland , by subjecting the workmen in these countries to an Injurious competition with Irish immigrants , trho , oft the principles we are advocating , might be employed at home to their own benefit and that of society ? Has tho interdiction of reproductive employment not perniciously affected all classes in England , by swelling the rates to ouoh an extent that , in numerous rural districts , vrhen

-

-

Citation

-

Leader (1850-1860), Jan. 24, 1852, page 11, in the Nineteenth-Century Serials Edition (2008; 2018) ncse-os.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/periodicals/l/issues/cld_24011852/page/11/

-