On this page

-

Text (2)

-

¦¦ ¦ that of to put down lowing nassage:...

-

A BATCH OF BOOKS. The History of British...

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

-

-

Transcript

-

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

Additionally, when viewing full transcripts, extracted text may not be in the same order as the original document.

"History Of Political Literature. The Hi...

' * " *! . War ^ rP the v could possibly act : — attempting therefore , m * £ ^! f ^ ££ chManifested their baneful influence , at certain Sg £ ^ S cSKi «&^ theirrespective countries The ' Slowing is worthy of the reader ' s considerat ion on the same sub-^^~ i ,- n a Tjrecedinff chapter , teferrea to the influence of the writings of the Chrtian ^ ather ^^ omfcal opinion generally . The numerous , ^ houg h detached ?? w «« heathen legislation contained in these writings , produced a powerful effect onin ^ de ^ antoi ^ f men in the course- of time ; and gradually prepared the way ? oValr ^ £ teXS on the part of the Church , in the direction and improvement . f I ^ i Xirs The reUlar organisation of the clergy ; the numerous and interesting pSK ^ Sssi o ^ vftal questions of doctrine and discipline ; the V" ™* * £ ***( KZt manifested in their synods and councils ; the inquiries and investigations , Sfh dS ^ d ^ directly i nstituted , on the political questions of the day at such m ^ merou ? theologica l gatherings ; the necessity imposed on all ^^^ Jfgg to the practical operate of the broad principles of legislation , as ^ J ^**^™ own , and their people ' s lives and property ; the learning , talent , and eloquence dis-Sed in the management of their own ecclesiastical affairs ; the constant and em-Shatic appeals madetothe common sense and common feeUngs of mankind onwhat-? home to their -day necessities and duties ; the heroic , andenhghtened

Ser cam every . _ pT ^ oTm ^ p ^ d ^ gre ' - nationirexigencies by Christen communitiesgenerall y ; ? U these , and a thousand sources of influence , gradually drew civil power into religious channels ; a circumstance which , when looked at from a certain point of view , may be justly and incontrovertibly pronounced as the first decided mark of improvement in the political progress of mankind . What eoes commonly under the denomination of Papal authority , was , then , onginallv the almost necessary result of Christian influence on heathen systems of government . It was the embodiment of the protests , appeals , rights , and privileges which took their rise out of the struggle Christianity had to make for some centuries against lone and firmly-established systems of political misrule and oppression . The more widely the gospel scheme became extended , the more political power ^ influence it conferred upon those who were the delegated instruments of guiding and directing its public movements and concerns . The active and stirring members of the Church had religious constituencies , augmenting in number and authority year after year ; and tinVjrradually increasing power sapped the foundation of the old bulwarks of civil politv , and made them yield to the remonstrances and moral force of these zealous and rational innovators . The clergy and their flocks were , in fact , a Christian republic , grounded on a novel set of political principles , rising into authority and independence aniidst the mass of barbaric and heterogeneous elements , which the old civilisation of

"the world presented . Mr Blakey gives a pretty full account of the anti-papal movement , which w * s much more potent and significant in the early ages of our modern history than is generally supposed . After speaking of early political satires , he gives the following summary of the views on this subject of the late distinguished-Signor Kossetti , whose theories on the political significance of eaSy Italian literature have excited , during the last thirty years , much attention : — - , , ,. There has been a good deal of light thrown in recent times , on-the general question as to the allegorical character of the chief Italian poets of the fourteenth century by the publication of Signor Rossetti ' s works . He has with g * 5 Ht learning and candour devoted many years to the consideration of the subject . The general conclusions to which he has arrived , relative to the double or political meaning of these poetical effusionsmay be statedfrom his own work , in the following terms .

, , The greater part of these literary productions , liitherto looked upon as mere works of amusement , as romances , love verses , or even formal and ponderous treatises , are writings which embody certain hidden doctrines and mysterious rites , transmitted from early ages ; and that these portions of their contents , bearing the appearance of fantastic fables , contain amass of unknown history , expressed in particular symbolical characters or terms , calculated to preserve the memory of the secret labours of our ancestors . The obscurity which pervades these works is remarkable , and purposely effected by profound study . The most eminent literary men of various ages and languagesinEurope , * "were pupils inthis mysterious school ,- which f never-losing sight-of i ts principal object , sought out distinguished talents in order to induce their possessors to co-operate in the bold design . The modern civilisation , or political progress ^ of European Btates , is mainly attributable to the incessant labours of this school , which produced a vast number of works fitted for the instruction of nations , and for preparing the public mind for great changes and events . It was chiefly by the unwearied

activity , and innumerable proselytes of this school of reform , that the seeds of a deep hatred against Rome were disseminated throughout Europe for many centuries , which prepared the way for that explosion of opinion and doctrine which shook the Vatican to its centre , and ushered in the Reformation in the several countries of Christendom . The foregoing passages are from the first volume . In the second our author sketches the history of political writing from the year 1400 to the year 1700 , beyond which the present volumes do not extend . He adopts the same plan here that he did in his Philosophy ' , giving brief summaries of the systems of the various men , with the dates of their lives and labours . This plan gives the work , at all events , the utility of a handbook , to which the general reader may refer occasionally , when he would learn the place of a political writer in the history of his science . We extract the following , because it is by no means generally known how important a place the Treatise of Buchanan ' s holds in literature—though Dryden , by the way , has had the liberality to indicate Milton ' s obligations to its author : —

George Buchanan . — " De Jure Regni apud Scotos . " This work of Buchanan ' s is worthy of especial notice , for the bold political statements it contains . It made a deep impression upon the political mind of Europe , at the time of its first appearance . The leading object of the work is , to < how that the royal authority of every country is derived from the people ; and that if kings and rulers do not perform their duty , but act falsely to the nation , they may be deposed and killed . Buchanan says , in reference to his book , " Do'Juro Regni , " " I have deemed this publication expedient that it may at once testify my zeal for your service , and admonish you of your duty to the community . . . . Yet I am compelled to entertain some slight degree of suspicion , least evil communication , the alluring nurse of

the vices , should lond an unhappy impulse to your tondor mind ; especially as I am not ignorant with what facility the external senses yield to seduction . I have , therefore , sent you this treatise not only as an advice , but even as an importunate , and somewhat impudent , oxhortor , to direct you at this critical period of life , safely past the dangerous rocks of adulation ; not merely to point out tho path , but to keep to it ; and If you should deviate , to reprove and reclaim your wanderings ; which monitor if you obey , you will ensure tranquillity to yourself and your family , and transmit your glory to tho most remote posterity . " Buchanan ' s work is written in tho form of a dialogue ; and in that portion of it devoted to the consideration of the origin and nature of government , we find tho

fol-3 M ^ Thus seems . B . Does compact , doeS anything against his own stipulations ,- * reak his agreement ? M . He does . B . Sih ^ nV the bond which attached the king to the people " broken , all nghts . he ^ de-SsESmKSSKftSial ¦ fesesHsesajSnSSg ^^ is sie ly ^ heir enemy . B . Is there not a just cause of war against an enemy who has inflicted heavy and intolerable injuries upon us ? M . There is . _ ^ I ^ Jf J is the nature of a war against the enemy of all mankind , that is , against a tyrant I SNonSSej S . B . Is it not lawful in a war just commenced , not only for the whXpeople , butfor any single person to kill an enemy ? M . Itmnrtbe jmfessed B What then , shall we say of a tyrant , a public enemy , with whom all Sol mer . asternal ' warfare ? May not any one of all mankind inflict on him any Sty of war ? M . I observe that all nations have been of that opinion ; forTheba Fs S toUed for having killed her husband , and Timoleon for his brother ' s , and Cassius

f O ^ tieimp rrSnce of Buchanan ' s political works generally , Sir James Mackiatosh remarks , « The science which teaches the rights of man , the eloquence which ^ krndks thlsnirit of freedom had for ages been buried with the other monuments of the wisdomS % lcs ofThe genius of antiquity . But the revival of * $ *«*« " * ££ only to a few the sacred fountain . The necessary labours of criticism ; A " * ** £ - graphy occupied the earlier scholars , and some time elapsed before the spirit of «* £ quitywas transfused into their admirers . The first man of that penod , whatunted elegant learning to original and masculine thought , was Buchanan ; and he . too , Z / to nave been the first scholar who caught from the anciente the noble flame of republican enthusiasm . This praise is merited by his neglected , «^ . ! mw ^ tract , < De Jure Regni , ' in which the principl es of popular politics , and ^ "J ™" a free government , are delivered with a precision , and enforced with an energy , which no former age had equalled , and-no succeeding has surpassed . Mr . Blakey should have given us the date of the De Jure , & c . It was

published in 1579 . . ,. - ' _ . * ¦ i Mr . Blakey does not , we observe , give every writer his fair proportional space , according to his literary importance . Algernon Sidney has only halt a page-less thfn the eccentric John Gilburne . Jeremy Taylor has but a paragraph-though the Liberty of Prophesying deserves much more . Mr Blakey , too , should have been much fuller in pointing out the difference between " Republicanism , " as it was conceived by the Sidneys and Miltons , and what is now called " Republicanism" in Europe . It is just his deficiency in such points as this which prevents us from being able to pronounce his book a high-class one—though , let us repeat , we respect his intentions and his industry , and think that he deserves credit for selecting a suoject so much in . need of illustration .

. . We shall conclude with a paragraph , which we do not insert because it has a tendency to magnify pur office of journalists , but because it really contains what is substantially true—though expressed somewhat

magmloquently : — ¦ ¦ '' ?'¦» And here we shall take the liberty of making a remark or two on the political writers of our own country , to whom we are , at this hour , under such weighty obligations . We ore apt , as a nation , it has been often said , to set a high value on our literary labours , in almost every department of human inquiry ; and not , perhaps , without some good grounds for this national partiality . But making due allowance for whatever may be overcharged hi our estimates on this point , we think it will not be deni ed by any qualified to sit in judgment on the question , that the political literature of Great Britain , taken as a whole , and for the three centuries now under consideration , is superior to that of any other country . It is more varied in its character , more profound and searching in its inquiries , more systematically arranged , and more copipusly and elegantly illustrated , than anything we can find in the other countries of Europe . It displays a much greaterportion of acute ££ 3 ' vigorousi intellect , than we can recognise elsewhere . Take the speculations of anyone of the continental states , and contrast its political disquisitions with those of our own hind , and we shall soon perceive the superiority of the latter in all that appertains to originality of conception , logical order , subtile analysis , and above all to the susceptibility of applying all political writing to the practical concerns of legislation and government .

There was likewise a vigour , and a capacity for sustaining efforts , displayed in the English mind which are not discernible in the political history of other nations . _ Indeed , when we contrast the personal courage , the lofty independence , the indomitable will , and the total disregard of consequences , when notions of duty were present , which stimulated the great majority of our writers to maintain their respective ideas of general polity , we cannot but see that they stand alone in the great theatre of political contention . They afford an interesting manifestation of the vast superiority of that national intellect , which is alike at home , whether in matters of theory or in practice . They have proved shining lights to all other nations . As a country we stand on a commanding eminence as cultivators of political knowledge . The writers of England have stemmed the tide of intolerance and ignorance , and burst asunder the fetters which would have confined our minds as well as our bodies in hopeless

subjection . The vindication of general liberty , and the preservation of everything valuable in society , have been the fruits of their pen . Amid the fierce controversies of the day , and the collision of intellects , they have invariably been guided by the loftiest ideas of personal freedom , and national independence .

¦¦ ¦ That Of To Put Down Lowing Nassage:...

¦¦ ¦ that of to put down lowing nassage : — " B . Is there , then , a mutual compact between the king and the P it not he who first vi olat es the and THE I , E A PER- ffATUia > AY , II I II If a mutual compact between the king and ffie

A Batch Of Books. The History Of British...

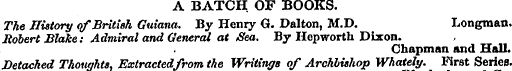

A BATCH OF BOOKS . The History of British Guiana . By Henry G . Dalton , M . D . Longman Robert Blake : Admiral and General at Sea . By Hepworth Dbcon . Chapman and Hall Detached Thoughts , Extractedfrom the Writings of Archbishop Whately . First Serieo , Blackadcr and Co Later Years . By tho author of " The Old House by the River . " Sampson Low and Son . Studies from Nature . By Dr . Hermann Masiue . Translated by Charles Boner . Chapman and HalL Talpa t or , the Chronicles of a Clay Farm . By Chandos Wren Hoskyns , Esq . Third Edition . Lovell Reeve . The History of British Guiana is a book which ' must have cost tho author vast lubour , and which essentially deserves to be classed among tho useful works of modern literature . Doctor Dalton arrived at the colony , with the purpose of residing there , in tho year 1842 . Naturally desirous to know something of the

-

-

Citation

-

Leader (1850-1860), Jan. 13, 1855, page 20, in the Nineteenth-Century Serials Edition (2008; 2018) ncse-os.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/periodicals/l/issues/cld_13011855/page/20/

-