On this page

-

Text (2)

-

Untitled

Untitled -

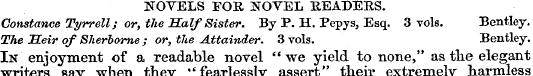

NOVELS FOE, NOVEL READERS Constance Tyrr...

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

-

-

Transcript

-

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

Additionally, when viewing full transcripts, extracted text may not be in the same order as the original document.

Todd And Bowman's Physiology. The Physio...

Fahrenheit ; but sometimes , when the exertion has been continued for five minutes ( as the biceps of the arm , in sawing a piece of wood ) , it has been double that amount . This development of heat may be in a great measure attributable to , and even a necessary consequence of , the friction just alluded to . " The idea of soft moist semi-liquid fibres producing this heat by friction is one that we confess astounded us , coming from such writers . We were less surprised at finding them fall into the old routine of separating mind from the brain , and making it an independent existence , because they bring the authority of " Revealed Truth" into the field—ah authority which , in matters of science especially , is most unhappy . Their treatment of this subject , however , is such as we observe in a large class of orthodox writers : their facts and arguments all go one way , their conclusions another . No positive Biologist would desire a more specific st atement than this : —

" From these premises it may be laid down as a just conclusion , that the convolutions of the brain are the centre of intellectual action , or , more strictly , that this centre consists in that vast sheet of vesicular matter which crowns the convoluted surface of the hemispheres . This surface is connected with the centres of volition and sensation ( corpora striata and optic thalami ) , and is capable at once of being excited by , or of exciting them . Every idea of the mind is associated with a corresponding change in some part or parts of this vesicular surf ewe ; and , as local changes of nutrition in the expansions of the nerves of pure sense may give rise to subjective sensations of vision or hearing , so derangements of nutrition in the vesicular matter of _tliis surface may occasion analogous phenomena of thought , the rapid development of ideas , which , being ill-regulated or not at all directed by the will , assume the form of delirious raving . " Elsewhere it is said : —

" Although the workings of the mind are doubtless independent of the body , experience convinces us that in those combinations of thought which take place in the exercise of the intellect , the nervous force is called into play in many a devious track throughout the intricate structure of the brain . How else can we explain the bodily exhaustion which mental labour induces ? The brain often gives way , like an overwrought machine , under the long-sustained exercise of a vigorous intellectual effort ; and many a master mind of the present or a former age has , from this cause , ended his days ' a driveller and a show / A frequent indication of commencing disease in the brain , is the difficulty which the individual feels in ' collecting his thoughts , ' the loss of the power of combining his ideas , or impairment

of memory . How many might have been saved from an early grave or the madhouse , had they taken in good time the warning of impending danger which such symptoms afford ! The delicate mechanism of the brain cannot bear up long against the incessant wear and tear to which men of great intellectual powers expose it , without frequent and prolonged periods of repose . The precocious exercise of the intellect in childhood is frequently prejudicial to its acquiring vigour in manhood , for the too early employment of the brain impairs its organization , and favours the development of disease . Emotion , when suddenly or strongly excited or unduly prolonged , is mast destructive to the proper texture of the brain , and to the operations of the mind "

The quiet assumption of the opening sentence about the independence of the mind , is made with reference , w e presume , to " Revealed Trutb ;" and if the rest of the passage flatly contradicts it , " so much the worse for the facts . " Logic is not the forte of these writers , aa we may note in the following extraordinary passage : " The nature of the connexion between the mind and nervous matter has ever been , and must continue to be , the deepest mystery in physiology ; and they who study the laws of Nature , as ordinances of God , will regard it as one of those secrets of his counsels ' which angels desire to look into . ' The individual experience of every thoughtful person , in addition to the inferences deducible from revealed Truth , affords convincing evidence that the mind can work apart from matter , and we have many proofs to show that the neglect of mental cultivation may lead to an impaired state of cerebral nutrition ; or , on the other hand , that

diseased action of the brain may injure or destroy tbe powers of the mind . These are fundamental truths of vast importance to the student of mental pathology as well as of physiology . It may be readily understood that mental and physical development should go hand in hand together , and mutually assist each otber ; but we are not , therefore , authorized to conclude that mental action results from the physical working of the brain . The strings of tbe harp , set in motion by n skilful performer , will produce harmonious music if they have ; been previously duly attuned . But if tbe instrument be out of order , although the player strike the siuiie notes , and evince equal skill in the movements of his lingers , nothing but the harshest discord will ensue . Ah , then , sweet melody results from skilful playing on a well-tuned instrument of good construction , so a sound mind , and a brain of good development and quality , are the necessary conditions of healthy and vigorous mental action . "

I he individual experience of every thoughtful person affords . _convincing evidence of mind working apart from matter , we are told . But ; where is the evidence H Who ever witnessed the phenomena of thought when no nervous matter was present P Name your authority ( we decline ** Revealed . truth" ) , give a single instance , give a single argument . All we know of nnnd is in connexion with a living brain . Give us an instance of u brainless mind , and we will thankfully acknowledge it . Rut the logic of what follows is peculiar . We are fold that there is evidence , apart from Revealed Truth , of the independent existence of fhe mind , " and we , have many proofs to show that the neglect of mental cultivation may lead fo an impaired state of cerebral nutrition . " This and , is very noticeable . So , indeed , is the whole passage . The more clearl y to expose its _1 ' aJla . cy we call attention to this exact _parallel _.

I hat Strength bits an existence independent of mere matter , will bo evident to the experience of every thoughtful person , though Revealed truth is silent on tho point ; and we have innumerable proofs tin tt neglect of the exercise of this Strength leads to an impaired state of muscular nutritiou ; so that a man who does not employ his strength will be found to have small and flaccid muscles ; while , on the otber hand , as a further proof that Strength is independent of muscular fibre , any disease of the muscular fibre will derange or totally destroy the powers of tbe muscle . At is true that physical Strength and wwc _\ _iW development go hand iu

Todd And Bowman's Physiology. The Physio...

hand , but we are not to conclude that Strength results from the physical action of the muscles ! We have formerly shown that mental phenomena are the peculiar phenomena of nervous tissue , as muscular actions are of muscular tissue , and we refer hesitating readers to that exposition , especially those who may conclude from what has just been said that we are " materialists . " ( No . 124 , p . 762 . ) Having made these objections , let us cordially commend the excellencies of this work : these are , great clearness and minuteness of exposition , exhaustive erudition of what has been done by previous writers , great care in the examination of dubious evidence , impartiality in stating conflicting views , candour , and , above all , valuable original matter . Mr .

Bowman is a first rate microscopist ; and this work bears ample testimony to the original observation and experiment of the authors . High praise this , and deserved . If the work do not exhibit great philosophic merit , it exhibits such practical excellencies , that no student should be without it . The chapter on the tissues , though very deficient in philosophic grasp , is valuable for the minuteness of its details ; the chapters on Innervation are also eminently useful , especially that on the reflex action of the nerves . Indeed , the importance and space given to the nervous system in this work entitle it to be considered in the light of a monograph . On the completion of the work we may return to it , and examine its chapters on vegetative life , for which space at present fails us . The illustrations also deserve a word of praise : they are very numerous , many quite new , and all admirably engraved .

Ar01903

Novels Foe, Novel Readers Constance Tyrr...

NOVELS FOE , NOVEL READERS Constance Tyrrell j or , the Half Sister . By P . H . Pepys , Esq . 3 vols . Bentley . The Heir of Sherborne ; or , the Attainder . 3 vols . Bentley . In enjoyment of a readable novel "we yield to none , " as the elegant writers say when they "fearlessly assert" their extremely harmless opinions . But the novel must be readable , and " there ' s the rub" ( to use an elegant and unfamiliar quotation ) . So few novels are readable , after one has had a certain experience of circulating libraries . It is pleasant enough at first : the youthful mind has profound faith in the Reginalds and Claras ; ignorance of the world lends a willing ear to the conversations which novelists liberally employ ; and an ardent imagination believes in the probability and practicability of all the " adventures . " But the illusion vanishes . Experience comes to teach us that life is supremely unlike the circulating library ; and the very abundance of the

circulating library painfully teaches us t _& at it is very like itself , so that after awhile we know exactly what turn the story will take , what the villain will do , what the wronged but haughty beauty will say , what misery the lovers will finally emerge from into festal joy , and wdiat escapes will diversify the " adventures . " Had we never read more than a dozen novels we should eagerly " devour " Sherborne ; or , the Attainder , an historical novel of the most approved type , but owing to the cause just hinted we found it totally impossible to get through more than the first volume . The author will rebel , no doubt , at this the critic ' s " unfairness . " But after all , is not that unreadability sufficient criticism ? We asked nothing better than to accompany him gaily to the end of his third volume ; but it is not our fault . You cannot induce the pastrycook ' s boy to dine off raspberry puffs ; he has had his surfeit long ago , and would prefer a little plain bread and cheese .

Then , as to Constance Tyrrell , we remember the day when such a novel would have been wept over , when Reginald Mowbray would have been the secret ideal and Constance the avowed idol of our " imaginings " ( whatever that may be ) ; but , alas , the day ! we cannot command sufficient naivete and credulity now , and . vthis novel , like so many others , we put down unfinished—a _ipui lafaute ' l To those whose appetite is stronger , and whose experience of novels is more limited , we may recommend these two books ; they are neither better nor worse than hundreds of others , but to us possess the incurable sin of not being real ; they are like no life but that which moves through

three volumes or five acts—the library and the stage . All tho characters remind us of the " characters" of the celebrated Mr . Marks— " One penny plain , twopence coloured , " which characters also were the glory of our 3 outhful days ! Apropos of youth , Mr . Pepys must be a very young man , or he would never have fallen into that novelist ' s error of calling Mason old at forty . Think of a man being necessarily excluded from a girl ' s alfections because lie is forty—what immense ignorance ! It is , however , the conventional belief of the circulating library , where a man after _five-and-twenty , and without black moustache and raven ringlets , has a feeble position . Ami see what comes of being forty and proposing to one ' s cousin ! Here is a serious man seriously declaring his love , and

"Ibe only reply vouchsafed to him , however , was a loud burst of ringing laughter that made the very walls resound again . Mason started to bis feet , and paced up and down the room , his blood boiling at tbe insult , but his usual selfcommand still enabling him to preserve outward composure , that no hurst , of irritation on bis part might contribute ; to the downfal of his hopes , which now seemed ho momently impending . He bit , bis lips almost through , and waited impatiently till Constance _shouljl recover from ber fit of laughter , and give him some definite reply . This , however , she did not , seem to find it easy to do ; one paroxysm succeeded another till ber eyes were running over with _lears , and sheer exhaustion at length brought , the fit ton conclusion . The indignant aspect of Mason's countenance , as he paced up and down tbe room , servedonly to add to ber amusement , and she seemed on the point , of indulging in another outburst , when she checked herself , and said :

"' 1 really beg your pardon , James , for receiving your serious proposal with such ill-timed hilarity ; hut , I assure you , it was too much for inc . I could not resist ,. Why , my dear , fond , venerable cousin , what could possibly have possessed you to think that you were endowed with qualities likely to captivate a gay young thing like me , or to believe tbat I was likely to make u suitable wife for you ? But 1 cannot believe you were serious : you wanted to see how I should behave when you went through the solemn furce of making mo a formal proposal . In that case , 1 _liopo you arc us much gratified as J have been at tho _micccwful manner iu which

-

-

Citation

-

Leader (1850-1860), Sept. 11, 1852, page 19, in the Nineteenth-Century Serials Edition (2008; 2018) ncse-os.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/periodicals/l/issues/cld_11091852/page/19/

-