On this page

- Departments (1)

-

Text (5)

-

40 TH-E IiSADEB, [No. 355, SATURgAr ^

-

.. jTtJJtflttttiL- '

-

Critics are not tie legislators, but the...

-

Os our table, as on the table of many a ...

-

THE ENGLISH OF SHAKSPEARE. , The English...

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

-

-

Transcript

-

Note: This text has been automatically extracted via Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. The text has not been manually corrected and should not be relied on to be an accurate representation of the item.

Additionally, when viewing full transcripts, extracted text may not be in the same order as the original document.

40 Th-E Iisadeb, [No. 355, Saturgar ^

40 TH-E IiSADEB , [ No . 355 , SATURgAr ^

.. Jttjjtflttttil- '

^ ^ TMtimxt .-

Critics Are Not Tie Legislators, But The...

Critics are not tie legislators , but the judges and policeof literature . Theydo not , , make laws—they interpret and try to enforce them . —Hcttnburffh Jleview .

Os Our Table, As On The Table Of Many A ...

Os our table , as on the table of many a club and reading-room , lies a pile of periodicals , which would furnish matter for weeks of leisure if life had no more serious demands than that of whiling away the hours ; and certainly the great majority of our readers would eye this pile with something of that envy which , moves a small boy standing outside the pastrycook ' s shop , and contemplating the wealth of tarts that have so little power over the pastrycook ' s desires . In his impatience ,, one of these readers might taie up the British Quarterly , and having gone through the historical narrative which sets forth the " Great Oyer of Poisoning "—not without a passing reflection that those were terrible times , and that there is considerable satisfaction in

the consciousness of living in tiroes when judicial proceedings aTe so infi--nitely superior—he might be led by such train of tihought to open the Westminster Beview and read the article on " English Law -. its Oppression and Confusion , " because however he may be disposed to glorify the present age in contrast with t i e days of old , he must think meanly of it in contrast with the ideal in his mind , especially as regards Law . Or he might turn to another article in the same Review , attracted by the title , to learn what was revealed of the "Mjsteries of Cefalonia / ' and there he would be both amused and astounded at finding & Thackebay in the Ionian Islands , painting society there with the same keen , wholesome satire , and -with a sterner purpose , than Thacicerat . It is a very remarkable paper indeed ; and the extracts given fromt ~ he Greek satirist fully account for his exconarnuni cation by the Greek Church . The tone in which he addresses his Holiness has an earnestness no reader will mistake , while a certain Thackbbayish humour

plays about the sentences . Bead this sketch of the Greek Priesthood : ¦—" In the bosom of oar community , Right Reverend Father , there are to be seen certain persona wearing long , fall , Hack dresses , large beards , their hair unshorn after the fashion of woiiien , and a hat like a pot without a handle upon their heads . These , your Holiness , lave renounced the world ; that is to say , they have renounced the burdens of the community , and yet live amid the community , singing , eating and drinking , arid doing nothing . Nor is that all—idleness and solitariness easily slide into overbearingness : they maintain that -they are the depositaries of all religion , and as such desire in tlie name of the religion to exercise authority ove * us .

" Nowj if the Protestants allow tbeir priests a certain authority , that does not seem to me at all strange . The priests of the Protestants are men of education , learning , And morality ; so that their society is profitable , and the slight authority they possess beneficial . But for o-sm priests , how can we , if we have any sense , admit them into our houses , and allow them any authority over our families ? Their ignorance is proverbial { ignorante come unpretegreco ! is a European phrase ); their morals , before and after their ordinaHon , are notorious to us all ; and their education is that which ( hey picked up in their various unordained capacities of porters , boatmen , shopmen , or servants . Your Holiness need not tell me that the Holy Spirit by virtue of ordination has cleansed them from the old man , and created in them the new man ; your Holiness and I may believe this , but there are many who don ' t !" This last touch is admirable . Here is a passage as applicable to Ireland as to Iotiia : —

" Among the other articles which are sold in these religious repositories are the prayers for the sick . Whenever one of his parishioners' wives has a sick child , the minister , who'has previously taught her the necessity of such prayers under the circumstances , receives twelve , fifteen , or twenty obols for performing one—for uTging < Grod to restore to health the child of the woj & an who has given him the aforesaid obols . " Let your Holiness suppose that you had received power as vicegeient of the Most High , to heal according to your own judgment , whenever benevolence or charity might move you thereto . Suppose that my child -was sick , and that I and his mother came before you on our . lnees , weeping out our very hearts' blood ; that you saw us wasted with , our griefs , and sorrowing for the danger of a b « ing that ( under

God ) we ourselves bad created , a darling on whom we bad set all our love and all our souls ; even if your Holinoss in your wisdom did not think fit , or if your heart was not moved to grant our request , you would at least not hear ou . r cry with indifference , and your door would open to us nono the less easily on any other occasion . But if , in place of g ; oing mysolf to seek you , I were to pay somebody else sixpence to go instead and petition you to save my child from the danger—how much would you value such a prayer ? As I conjecture , you \ rould count it a sixpenny petition . You would hoar it with due contempt , and would be wroth with the uttexer and with me . Surely , God is not moved either by the conjurations of witches , or by the set forms of priests . He ia only pleased with the utterances of the heart ; and that is" a worship which none can offer better than he who has the grief in his heart . Paid-for prayers profit nobody excejt the receiver of the money paid for them . "

Having had enough of political and ecclesiastical matters , the reader may wish to refresh his mind with a little literature , and for this purpose he again recurs to the British Quarterly , and leads a pleasant retrospective review of Sir Thomas Bkownb , one of the quaint worthies of our Literature ; or ho may be attracted by the article on WoitnswoRTH in the National Review , a philosophical disquisition on a subject which seems inexhaustible ; having learned with this writer to enter into Woudsworth ' s meditative spirit , he may pass on to another article in the same review , on Bamac , a poor article indeed , made up from LIjon Gozlah ' s charming littlo volume , Balzac

* n Panfoujtes , but as the majority of readers hove not seem , and will not see the volume , the article will put them in possession of some amusing details , and somewhat modify their conceptions of the great novelist , who , by the ^ ray , is very pedantically and unfairly treated in the last Mevue des Devx Mondet . In th . o National alao there is a defence of Mr . Spuhgkon , and an attempt to show why Sptieoeonism and Calvinism impress thousands in * p ito « if common sense , and let us add , in spite of healthy moral instinots . On the whole this ia , in our opinion , the poorest number the National hue issued , containing no one artigle Jjftoly to pxcfto jnuch . attention ,

The reader , if attracted by science and its applications , will find m the Westminster a paper on " Boiling "Water , " containing an account of the Geisers of Iceland , and some of the curious phenomena of boiling watera paper valuable for its matter , but heavily written—and in the British Quarterly a paper on " The Smoke Nuisance—its Cause and Cure , " which to all inhabitants of large cities will be of great interest . The politics and polemics of the Reviews will also find readers ; but more literary inclinations will lean towards the article on c ' Worldliness and Other-worldliness " in the Westminster , wherein the poet Yovng is criticized as man , poet , Calvinist , and moralist .

Having come to the end of these Reviews , he may attack a fresh pile , and begin with the new Magazine , the National , a sort of pictorial Household Words , with matter of various tastes . Mr . Shirx / ey Hibbekd tells an interesting anecdote in his account of his Aquarium . The fish , crabs , reptiles in his tank are mostly furnished him by a wandering amphibious naturalist , who daily wades in the Lea or New Ifrver , and , although stone blind , is an expert huntsman , groping about with his hands , and thus catching the prey ; which done , he quits the water with his sole companion , a dog , and without stopping to dry his clothes wanders off in search of purchasers .

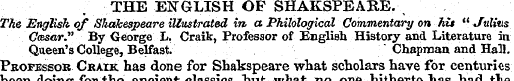

The English Of Shakspeare. , The English...

THE ENGLISH OF SHAKSPEARE . , The English of Shakespeare illustrated in a Philological Commentary on his " Julius Ccesar . " By George L . Craik , Professor of English History and Literature in Queen ' s College , Belfast . ' Chapman and Hall . Pkofbssok Ckaik has done for Shakspeare what scholars have for centuries been doing for the ancient ^ classics , but what no one hitherto has had the ingenuity to devise or the courage to execute for our greatest classic . Among the many erudite but almost worthless books written about Shakspeare , this small volume is conspicuous for learning , judgment , purpose , and direct utility . It consists of three parts . The first part , containing the Prolegomena , narrates the ascertained facts of Shakspeare ' s personal history , and the probable dates of the works ; discusses the sources for tlie text of the Plays ; enumerates the Shakspearean Editors and Commentators

and enters into the intricate subject of the Mechanism of English verse and Shakspeare ' s prosody . The second part contains the philological commentary . The third part is devoted to a reprint of Julius Casar , according to Professor Craik ' s recension of tbe text , with the novel and ingenious contrivance , which will doubtless hereafter be followed , of numbering the speeches . In the Greek plays the lines are numbered , and every student is aware of the immense benefit derived from this practice ; but in the Greek plays the speeches are constantly of so great a length that nothing less than numbering the lines would serve the student ' s purpose ; in modern plays , the brevity of tbe speeches , and the frequent occurrence of speeches less than a line in length , often merely of a word or two , suggest the propriety of Professor Craik ' s plan .

There is no one , except the happy possessor of a text utterly without notes , who has not . been irritated by the obtrusive twaddle , and the nonexplaining ingenuity of explanation , which , under tbe guise of commentary , editors foist upon Shakspeare ' s pages . In seven cases out of every ten the student gets no instruction on the point which perplexes him . Nothing is elucidated . What was dark before has become still more obscure . The editor has displayed his acquaintance with old copies and black letter literature ; meanwhile , the difficulty remains the same . In Professor Craik ' s commentary the student will find genuine erudition turned to a genuine purpose ; there is nothing set down for the sake of display ; authors are not quoted upon the slightest provocation ; parallel passages are only adduced as cumulative evidence . The object of the commentary is the English language , its structure , its meaning , its licences ; and no student of the English language and of Shakspeare will read it without clear profit . A passage or two will display the nature of this commentary , and for the sake of fairness , we will not select the best , but the most typical passages : —

If it he aught toward . — . All that the prosody demands here is that the word toicard be pronounced in two syllables ; the accent may be either on the first or the second . Toward when an adjective has , I believe , always the accent on the first syllable in Shakespeare ; but its customary pronunciation may have been otherwise in Iiib day when it was a preposition , as it is here . Milton , however , in the few cases in -which he does not run the two syllables into one , always accents the first . And he uses both toward and totdards . Again , on the next poge : — Your outward favour . —A marSn favour is his aspect or appearance . The word ia now lost to us in that sense ; but we still van favoured with well , ill , and perhaps other qualifying terms , for featured or looking ; aa in Gen . xli . 4 : — " The ill-favoured and lean-fleshed kino did eat up the seven well-favoured and fat kino . " Favour seems to bo used forjface from the Bamo confusion or natural transference of meaning between

the expressions for the feeling in tho mind and the outward indication of it in the look that has led to tho word countenance , which commonly denotes the latter , being sometimes employed , by a process the reverse of what we have in the case of favour , in the sense of at least one modification of the former ; aa when wo speak of any one giving something his countenance , or countenancing it . In this , case , bowovcr , it ought to bo observed that countenance has the meaning , not simply of favourable feeling or approbation , but of its expression or avowal . The French terms from which we have borrowed our fatoour and countenance , do not appear to have either of them undergone the transference of meaning which has befo ^ lon tho English forma . But contenance , which is still also used by tho French in th « sense of material capacity , has drifted far away from its original import in coming to signify one ' s aspect < xr physiognomy . It ia really also the aamo ward with tho French and English c < W « t nence and the Latin continentia .

Iho following is more exhaustive >*~ / had at Urf . —Lief ( sometimes written leef , or leva ) , in tho comparative liefer or lever , in the ijuporlative liefatt , is the Anglo-Saxon leaf , signifying dear . "No modern author , I feolJovo , " saya Homo Tooko ( Z » . of 1 \ 261 ) , " would now venture » ny of theao Avords in a serious passage ; and they seem to bo cautiously shunned or ridiculed In common conversation , aa a vulgarity . But they are good English words , nod more frequently used by our old English writers than any other wort yf * corresponding signification , " Tho common n ^ der / n substitute for lief \ g few . And for Reft *

-

-

Citation

-

Leader (1850-1860), Jan. 10, 1857, page 16, in the Nineteenth-Century Serials Edition (2008; 2018) ncse-os.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/periodicals/l/issues/cld_10011857/page/16/

-