Rebecca Sykes

Introduction

This essay explores the pedagogical opportunities for studying “pictures” that the Nineteenth-Century Serials Edition (ncse) presents. By focusing on Matthew (Matt) Somerville Morgan’s double-page wood engravings for Tomahawk (1867-70), a richly illustrated nineteenth-century satirical magazine, produced in close collaboration with Thomas Bolton, his friend and engraver, this article opens up the website to scholars and teachers within and outside nineteenth-century studies. It shows how a focus on “postmodernist” strategies of reproduction used by artists can enrich understanding of the techniques of replication at work in nineteenth-century serials, while also enabling students of contemporary art history to recognise older forms of media as part of the narrative of artistic appropriation. The article concludes it is the digitisation of nineteenth-century serials that opens up new readings of Morgan’s tinted wood engravings.1

Although the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth century may have been the great age of the English graphic, with William Blake posited as, in the words of cartoonist and critic Tom Lubbock, “the supreme joiner of text and image”, this essay hopes to increase awareness of the Tomahawk’s rich visual content among non-nineteenth-century specialists, and, most particularly its pedagogical potential.2 Indeed, Tomahawk’s was an especially graphically-oriented weekly paper and its appearance in the nineteenth-century media landscape was intended to offer a more visually radical, if politically conservative alternative to the by then more genteel Punch (established in 1841), a former and future employer to a number of the Tomahawk’s editorial and artistic staff. And while it is the Tomahawk’s large wood engravings that are the subject of this article, other visual elements, such as covers, illustrated mastheads, department headers, and advertisements are found across titles in ncse, along with other illustrations, including Morgan’s elaborate covers, found in Tomahawk.3 Most notably, the archive holds fifteen of the engraved portraits of radical figures issued for its subscribers by the Northern Star (1837-1852), a Chartist newspaper based in Leeds. In contrast to the satirical tradition that Tomahawk’s belongs to – its use of a cartoon “scalper” in its masthead is a clear symbol of intent – the Northern Star portraits, which include the poet Andrew Marvell and the radical politician Henry Hunt, as well as leading Chartists, framed its sitters in dignified, classical settings associated with a fine art tradition in order to establish the movement’s leaders as men of quality.

Certainly, as James Mussell phrases it, “neglect is rarely benign in the digital world”, and, as such, it is “only by granting digital objects the widest possible use” that “we give them the best chance of survival”.4 Studying Morgan’s “pictures” offers a valuable lesson in looking and one that can enable students to develop the skills of critical reflection, interpretation, and contextualisation of key art historical discourses. In what follows, I show how a twenty-first-century digital resource can become part of the story I seek to tell about the artistic strategy of appropriation and its place in contemporary art history. Similarly, these issues have the potential to teach digital literacy skills to students who use digital resources as part of a more direct engagement with nineteenth-century print culture.

Morgan began his career as a theatrical scene painter, but it is for his work as a political cartoonist for the satirical press that he is best known. Before embarking on cartoons and satires, Morgan developed expertise in illustrations for documentary reportage for mid-Victorian illustrated weekly papers, including serving as a war artist. This work, for the Illustrated London News and the Illustrated Times, manifested ‘a strong sense of social responsibility’ and reflected his radical politics, both of which informed his satirical work.5 By the time of his involvement with Tomahawk, Morgan had also cartooned for Fun, a successful imitator of Punch, as well as having pursued a more conventionally fine art career. Significantly, “Morgan always listed his occupation as ‘artist’”, and he maintained an exhibition space at the studio/lodgings he shared with Frederick Buckstone at Berners Street, London.6 The intention of this article is to demonstrate how Morgan’s cartoons can be read as part of a wide-reaching cultural tradition of reproduction and appropriation, a diachronic conversation between artists that stretches backwards and forwards in time.

“Pictures” and Nineteenth-century Reproductions

The images discussed here are not considered in their original form: that is to say, rather than the nineteenth-century hard copy single plate prints produced by Morgan and Bolton, the twenty-first century digital objects that appear on the ncse website will be my focus. Specifically, I hope to demonstrate the pedagogic potential of the digital objects that began life on the pages of Tomahawk, objects which can, to quote Mussell, “be displayed in multiple forms as the user chooses [...] allowing them to be integrated within other systems and repurposed” (pp. 7-8). Indeed, the argument proposed here is that Morgan’s work for Tomahawk presents an opportunity to those who use images in the classroom to teach their students to engage critically with the work of art in the age of digital reproduction, when digital objects can be copied and shared with the flick of a finger.

When the ncse archive was first digitised and it was necessary to generate bibliographic codes for the digital images being uploaded, an editorial decision was made “to avoid evaluation as much as possible in an attempt to limit the subjective nature of interpretation” (Mussell, p. 109).7 Crucially, the ncse digital resource categorises its images as “pictures”, a designation that is provocative for those familiar with the development of postmodernist visual art and, I intend to argue, generative given Morgan’s own employment of the strategies of reproduction and transcription associated with the Pictures Generation: a loose affiliation of American artists working in the 1970s and 1980s, known for their use of appropriation and montage and the critical analysis of media culture. Artists associated with the group included Jeff Koons, Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, Louise Lawler, Richard Prince, David Salle. Each of them shared an interest in the circulation of images in contemporary culture and a mistrust of ways that images signify, that is to say, to make meanings.

Significantly, the grouping took its name from Pictures, a 1977 exhibition organized by art historian and critic Douglas Crimp and shown at New York's Artists Space gallery. Writing in 1979, Crimp describes how

In choosing the word pictures for this show, I hoped to convey not only the work’s most salient characteristic – recognizable images – but also and importantly the ambiguities it sustains. As is typical of what has come to be called postmodernism, this new work is not confined to any particular medium; instead, it makes use of photography, film, performance, as well as traditional modes of painting, drawing, and sculpture. Picture, used colloquially, is also nonspecific: a picture book might be a book of drawings or photographs, and in common speech a painting, drawing, or print is often called, simply, a picture. Equally important for my purposes, picture, in its verb form, can refer to a mental process as well as the production of an aesthetic object.8The term postmodernism first appeared in the 1970s and was used to describe a wide range of artistic practices that collapsed the distinction between “high” culture and “mass” or popular culture. Postmodernist visual art is typified by an embrace of complexity and contradiction, and is notable for the way it brings into question the values of authenticity and originality taken for granted by previous generations of artists. Also significant is the importance assigned to the viewer in the determination of an art work’s meaning.9

It is possible to tease out a comparison between the postmodernist tactics of appropriation and repetition evident in the work of the artists selected by Crimp, and the methods of reproduction, as part of a deliberate aesthetic strategy, in both Morgan’s cartoons for Tomahawk, and the transformation of the original print objects into twenty-first century digital objects. Such an exercise can be productive in relation to students’ understanding of the status and behaviour of online “pictures”, as digital and aesthetic objects; and it allows teachers to pose the question: “does the meaning of an artwork change when it is reproduced”? Or is it only the material of the artwork that is transformed?

This article is informed by my experiences of teaching BA Fine Art students and undergraduate History of Art students, whose ability to read images I could not take for granted. For that reason, although this essay discusses the issues raised by the digitisation of nineteenth-century illustrations, it also firmly maintains the link between Morgan’s Tomahawk cartoons and the wider English graphic tradition – the arts of drawing, engraving, ink and brush. The Greek term graphein, meaning both to write and draw, is significant here given the thematic focus of transcription, as a method of reproduction, examined below, although in this instance I am less interested in laying bare nineteenth-century literary and visual conventions than in designing an exercise in how to read an image in the context of contemporary art history; specifically, how can Morgan’s Tomahawk cartoons be understood in relation to postmodernist “pictures”.

Digital objects, unlike digital resources, “know no users” (Mussell, p. 145) and, as such, can easily become detached from their online publishing source. This is because digital objects, in the form of digital images, are not surrogates for the physical material each represents but rather objects with an independent existence in digital culture.

Discussions about the status of digital images taking place in the context of New Media Art – artworks created using new media technologies – are instructive when thinking about the opportunities and challenges digital resources present to students and scholars alike. For example, artist and theorist Hito Steyerl encourages artists to embrace the traces of cropping and pixilation that can affect an image as it circulates through digital networks. In her essay ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’, for instance, Steyerl admires the “poor” image for its “dubious” genealogy:

Its filenames are deliberately misspelled. It often defies patrimony, national culture, or indeed copyright. It is passed on as a lure, a decoy, an index, or as a reminder of its former visual self. It mocks the promises of digital technology.10Steyerl finds the rapid proliferation and circulation of digital images that engender the paucity of information, visual or otherwise, appealing; online, nineteenth-century serials and Bruce Lee film clips, for instance, experience a kind of democratic levelling. And although Steyerl’s sketch is about as far from a model of academic best practice as it is possible to get, her words remain generative with regard to how the Tomahawk archive has the potential to speak to materiality debates current in contemporary art discourse:11

The poor image is no longer about the real thing—the originary original. Instead, it is about its own real conditions of existence: about swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities.12Crucially, for Steyerl, the “poor image” is “about defiance and appropriation just as it is about conformism and exploitation”, and it is to the evidence of “defiance and appropriation” in Morgan’s Tomahawk cartoons that this essay now turns.

The appropriation and repurposing of images is not a new phenomenon. Artists from all periods have taken inspiration from past artworks. The genealogy of Manet’s Olympia (1865), for instance, from Giorgione to the V-Girls, offers an especially compelling narrative for use in the classroom in light of Crimp’s claims that the beginning of modernism can be “located in Manet’s works of the early 1860s, in which painting’s relationship to its art-historical precedents was made shamelessly obvious”.13 It was, however, in the postmodernist period that the referencing of past artworks came to be deployed with a self-consciously critical intent when, to quote Crimp again, “the fiction of the creating subject gives way to the frank confiscation, quotation, excerptation, accumulation and repetition of already existing images”.14 Robert Rauschenberg’s Retroactive I and II (1964), for instance, was created using around 150 silk screens of popular subjects in a manner that anticipates the “cut and paste” culture of today. In addition, Diego Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (c. 1647-1651) is just one of the historical paintings that recurs in Rauschenberg’s prints; a work Rauschenberg “steals”, according to Crimp (p. 58), for his own Crocus (1962), Transome (1963), and Breakthrough II (1965).

However, it is striking how Rauschenberg’s methods also recall the mixed economy of nineteenth-century serials print culture, with its emphasis on accessibility and familiarity. For example, Mussell has described how, in reference to the Penny Magazine, an illustrated magazine aimed at the British working classes, “[t]ext and image were combined upon the page to recontextualize content from elsewhere, to relocate things – whatever they were (exotic animals, scenes, works of art) and wherever they were located (exclusive galleries, museums, the jungle, the ancient past) – within a mass-produced publication that could be bought” cheaply (pp. 76-7).

The degree of translation involved is compounded when we, as readers and lookers in the twenty-first century, encounter these images as digital objects. To elaborate, just as the issue of materials have, to some extent, been side-lined in Western art history, in part owing to the logocentrism of the discipline, so too do nineteenth-century illustrations, translated into digital form, become subordinate to language in some important respects. As Mussell describes it, “[d]igital images are not images at all but strings of linguistic information that describe how an image should be displayed on a monitor” (Mussell, p. 97). As such, “the dominant model for the republication of this [nineteenth-century] material – OCR transcripts and facsimile pages”, while providing access to a mediated version of the original, can risk subordinating “the visual to the linguistic as only the transcript is searchable” (Mussell, p. 113). Indeed, by cropping or formatting the image, or, as in this case of this article, “snipping”, or “grabbing” “pictures” out of a Portable Document Format (PDF), to categorize and divide a previously self-contained document into constituent parts, is to treat the image as data.

Nevertheless, while digital reproductions complicate the narratives of origin and originality, authorship and authority, that sustain Western art history, it is also possible to make the case that nineteenth-century strategies of replication – understood by artists as subsequent versions of a first version, similar but changed – may be regarded as important precursors to postmodernist techniques of reproduction. For example, Holman Hunt, like many other major Victorian artists, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown included, “made a living through autography replicas commissioned by patrons who frequently requested changes from the first versions”.15 Hence, as Julie Codell and Linda K. Hughes have argued, nineteenth-century replicas helped

to effect a cultural shift away from a shamanistic originality privileged by the Romantics to highly valued re-makings until modernism’s fetish of originality and self-consciousness about tradition – as in Ezra Pound’s ‘Make it new!’ – denigrated replicas. For postmodernism in turn, however, originality became suspect and replication was welcomed in postmodern cultural analyses.16These methods of nineteenth-century replication retain currency in contemporary art in the work of Oliver Laric; his copies of ancient sculptures made using 3D printers can be connected to the tradition of casting mediated through the open-source digital content ethos of collective reworking.17 As such, there are important links and comparisons that can be drawn out in a pedagogical setting between the “Pictures” Generation and the nineteenth-century culture of reproduction; these connections can be buried if we do not look beyond the twentieth-century when teaching postmodernist art history. For example, Tomahawk similarly “made use of the contemporary for its own ends” (Mussell, p. 78) by featuring topical illustrations that sought to capture, and satirize, a particular historical moment or event. For example, Morgan’s cartoon that appeared in the 15 January 1870 edition of Tomahawk, titled ‘Dissolving Views! Or, The Past and The Future’, is significant given this discussion’s emphasis on media technologies (figure 1). The cartoon shows “Old Father Time conjur[ing] up the shadows”, and we, his audience, “watch him as he moves the slides of his lantern, and old pictures dissolve into new – as 1869 gives way to 1870” [editorial]. Time’s lantern is in fact two projectors; one shows a “Fenian”, “a brutal demon more beast than man”, with the figure of a “happy landowner” outlined in white behind. The second “slide” shows Napoleon III of France waving the flag of constitutional government, an angel traced in white at his back.

Figure 1.

In addition, the close proximity of Morgan’s large illustrations to the pages of advertisements included in each edition of Tomakawk (figure 2), both spatially and practically, is compelling, given that the “Pictures” artists were deeply interested in the market place of images and their circulation; indeed, their work frequently, and deliberately, resembles advertising. More importantly, a number of Morgan’s cartoons appropriate works of art by his contemporaries as part of the discourse of journalism, and as part of his own work as a producer of graphic images; as, in his own words, an artist. If postmodernist artists blurred the distinction between high and low culture by adopting the visual language of mass media to create advanced art, then Morgan’s work presents an intriguing discussion point for use in the classroom. For example, some of the questions that Morgan’s work raises include:

- Are political cartoons, a popular and commercial graphic form, “art”?

- In what ways, if any, is “appropriation” different from stealing?

- How does a replicated image constitute a reply to a first version, and its reception?

Figure 2.

Examples for use in the classroom

Figure 3.

In a cartoon included in the 8 August 1868 edition of Tomahawk, Morgan “steals” from his contemporary Henry Wallis. Wallis’s Chatterton (1856, Oil on canvas, 905 x 1205 mm, Tate, London) was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856 and described by John Ruskin in his Academy Notes as “faultless and wonderful”.18 The painting shows the suicide of the poet Thomas Chatterton (1752-70) whose poisoning by arsenic, at the age of seventeen in his attic room in Gray’s Inn, cemented his reputation as a Romantic hero to many artists and writers. Significantly, Chatterton himself dabbled with creative forgery when he attempted, and briefly succeeded, to pass off his own work, copied onto old parchment, as that of an imaginary fifteenth-century poet and monk called Thomas Rowley.

While Wallis “may have intended the picture as a criticism of society’s treatment of artists”, Morgan’s translation of the original picture features a rather more wizened character who stands in for the figure of the editor “at rest”.19 Gone, for instance, is the delicate plant on the window sill, its single bloom turned to the open window, of Wallis’s original. Instead, we see the neo-Gothic tower of Big Ben, also a transcription, of sorts, that opened in 1859; and tendrils of smoke escaping from a recently extinguished candle on a table in the far-right corner of the room that spell out P-O-P-U-L-A-R-I-T-Y. Significantly, Morgan’s recontextualization of Wallis’s scene in order to conflate the roles of editor and artist occurred at a time when reproductive technologies were beginning to dispense with the figure of the artist as Romantic hero altogether.

A question for students might be:

- How are the values of originality, authenticity and authorship challenged by the practices of appropriation and pastiche?

Figure 4

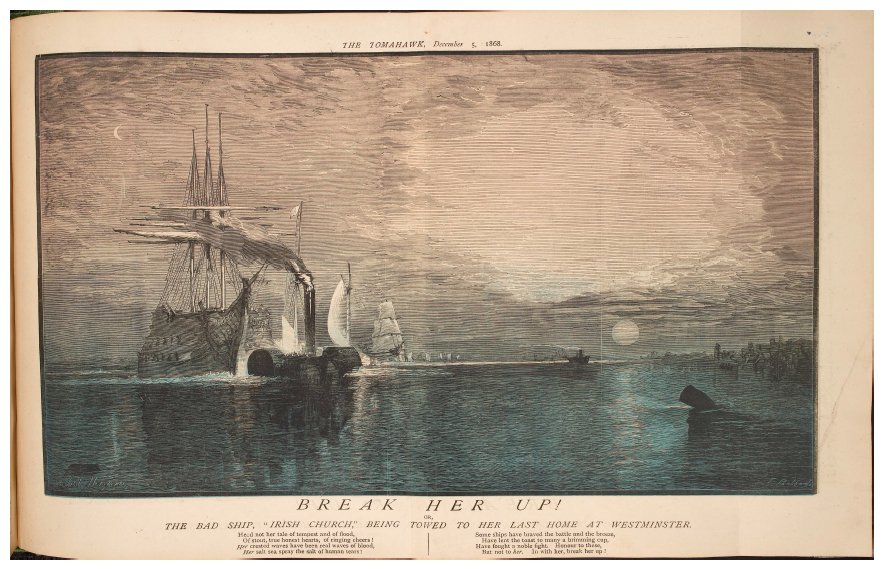

In contrast is Morgan’s version, composed in 1868, a year before the Irish Church Act, an important step towards dismantling the Protestant Ascendancy. The illustration’s accompanying caption reads: “‘Break Her Up!’, or, The Bad Ship, ‘Irish Church’, Being Towed to Her Last Home at Westminster”. In the cartoon, the sky is a curtain of dark greys and blues, with a gaping hole at its centre that threatens to swallow the scene whole.

For a more contemporary instance of the image’s transcription, this time in the medium of digital motion picture, note how Turner’s painting of the Temeraire was used symbolically in the film Skyfall (2012), when James Bond’s (played by actor Daniel Craig) age and fitness for service were recurrent themes:

[Bond is sat on a bench in the National Gallery. He faces The Fighting Temeraire. A scruffy-haired young man wearing glasses approaches and sits next to him.]

Q: It always makes me feel a little melancholy. Grand old war ship, being ignominiously hauled away for scrap [sigh]. The inevitability of time, don’t you think? What do you see?

Bond: A bloody big ship.22

A question for students:

- How does an image accrue meaning(s) when reproduced in different mediums?

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

It is significant, given Holman Hunt’s role in the story of nineteenth-century reproduction, that Morgan chose to reimagine two of Hunt’s paintings while drawing for Tomahawk. Specifically, in the issue of 20 March 1869, just one year after Hunt completed his painting Isabella and the Pot of Basil (1868, Oil on canvas, 187 cm x 116 cm, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne), itself a depiction of a scene from John Keats’s narrative poem ‘Isabella, or the Pot of Basil’, Morgan transformed it into a cartoon about Queen Victoria’s absence from public life: “Britannia’s Pot of Basil”.23 In Morgan’s version of the scene Britannia’s tears are those of T-R-A-D-E, while a depressed-looking Lion of England mopes at her side.

Moreover, Isabella and the Pot of Basil, “a design which every black-and-white artist is doomed to attempt sooner or later”, is a significant work in the story of artistic transcription, owing to its repeated recurrence in works of visual art from this period.24 For instance, while Hunt himself painted another, smaller version of the 1868 original the same year, other notable examples of transcription of Hunt’s picture include the Pre-Raphaelite painter John William Waterhouse’s Isabella and the Pot of Basil (1907, Oil on canvas, 104.8 x 74 cm, collection: H. W. Henderson, Esq.); Isabella and the Pot of Basil by Edward Reginald Frampton (1867, Tempera on canvas, 18.5 x 20 inches); Isabella and the Pot of Basil by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale (Drawing, c. 1898); Isabella and the Pot of Basil by Henrietta Rae (1897).25

In addition, Morgan chose to translate Hunt’s The Scapegoat, which exists in two formats, into another cartoon about the Irish Church (17 April 1869). Hunt painted a smaller version with bright colours and showing a dark-haired goat and a rainbow (The Scapegoat, 1854-5, Oil on canvas, 33.7 cm x 45.9 cm, Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester), and a larger version in more muted tones with a light-haired goat (The Scapegoat, 1854-6, Oil on canvas, 86 cm x 140 cm, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight). Both were created over the same period, with the smaller version being described as “preliminary” to the larger version, the one that was originally exhibited. Interestingly, a common complaint amongst contemporaneous critics was that the symbolism behind the picture – the painting shows the Jewish ritual enacted on the Day of Atonement, as described in the Book of Leviticus, when a goat would have its horns wrapped with a red cloth, representing the sins of the community, and be driven from the city – was too opaque.26 Nevertheless, Hunt’s picture possesses an enduring appeal; indeed, as recent as 2001, the cartoonist, collagist, and critic, Tom Luddock produced ‘After Holman Hunt’ (2001), made one month after September 11, with a shaggy Afghan hound as the scapegoat.

Morgan’s 1869 reproduction is evidently modelled on the larger version of Hunt’s original. The “scapegoat” at its centre – “unclean, less from its own individual misdeeds than for the injustice and tyranny of which it is the visible token” [caption] – looks less parched and abandoned than malignant; the words “Irish” and “Church” have been branded across its horns.

A question for students:

- How do the meanings of a picture survive its reproductions?

Conclusion

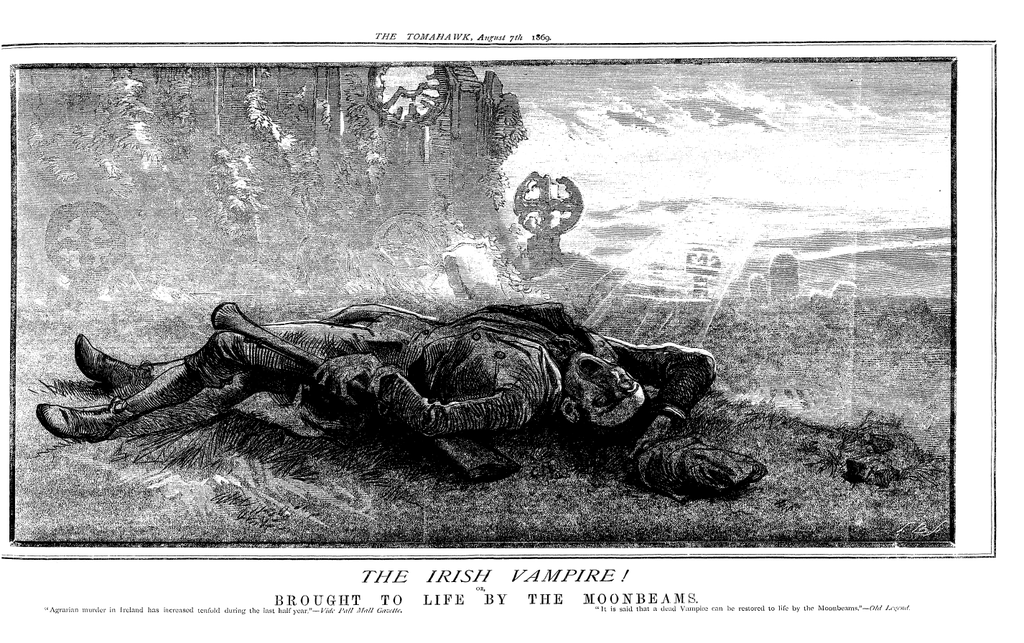

Finally, Morgan’s cartoons frequently came into conversation with the languages of literature and theatre, Shakespeare and pantomime alike. References to Gothic-inspired literary works are especially recurrent and Morgan regularly leant on the “the literature and stories of the diabolical” to portray Fenianism, in particular, with two cartoons devoted to “The Fenian Faust!” (1 and 29 February 1868), for example.27 “The Irish Vampire”, who writhes beneath the glare of moonbeams, appears in another (7 August 1869) (Figure 7), while the 18 December 1869 edition imagines an especially hideous “Irish Frankenstein” (Figure 8): “The Monstrous Legacy. An Old Legend in New Form” [editorial].

The repertoire of monsters that feature in Tomahawk, animal heads on human bodies appear with startling regularity, speak to a recognised trope of the Gothic: the putting together of “two things that should have remained apart”.28 In comparison, the “liminal space” of the nineteenth-century theatre, where established categories, like class, were “constantly blurred”, arguably performs a similar trick.29 Indeed, Morgan was a celebrated theatrical scene painter, designing sets for the 1864 annual Christmas pantomime at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, for example, and the theatre provided the setting for a number of his gothic-inspired cartoons. Notably, in an illustration designed to accompany the 13 February 1869 editorial (Figure 9), which attacked those, including the then Lord Chamberlain, who would allege impropriety regarding the increasingly, by the time of the 1860s, risqué (“French”) costumes of the decorative “female ‘fairies’, and the exotic scenes in which they were included”.30 Captioned “‘Propriety’ Behind the Scenes!”, the cartoon, which was itself a reproduction of one of Morgan’s (now lost) canvas paintings, Behind the Scenes (exhibited at The German Gallery, London, in 1870), shows female performers dressed in men’s clothes, “high-necked jackets and full-length trousers”, underneath their silvery tulle skirts.31 Performing dogs, also wearing trousers, look up imploringly at a Harlequin leaning against a table on which an assortment of oversized-masks and animal heads sit.

This outrageous technique of interpolation, the insertion of something of a different nature into something else, is, I would argue, indicative of both Morgan’s fantastical illustrations and the postmodernist methods employed in this essay. I think Morgan’s cartoons, which put together apparently incongruous images and discourses, offer encouragement to teachers who wish to think along parallel lines and use similar methods of reproduction in the classroom, in order to, in the words of the poet Jamie McKendrick, traverse art history, “finding precedent and prolepsis” that speak to our contemporary selves.32 Ultimately, it is the digitisation of nineteenth-century serials that opens up the possibility of reading Morgan’s pictures, and their reproductions, as part of the story of postmodernism, and the opportunity to think diachronically in the classroom.

Figure 7.

Figure 8.

Figure 9.

Notes

1 For more about Tomahawk, see the article in ‘About the Titles’ here [back].

2 Tom Lubbock, English Graphic, ed. by Marion Coutts (London: Frances Lincoln Limited, 2012), p. 41 [back].

3 Extant covers by Morgan appear in ncse in the runs for 1869 and 1870. For examples see the cover for 15 May 1869 here and 9 April 1870 here. For more about the Images in ncse, see the article ‘Visual Material’ in the ‘Editorial Commentary’ here [back].

4 James Mussell, The Nineteenth-Century Press in the Digital Age (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p. 22 [back].

5 See Brian Maidment’s entry on Matt Morgan, DNCJ, ed. by L. Brake and M. Demoor (Ghent and London: Academia Press and the British Library, 2009), pp. 425-426 [back].

6 Richard Scully, ‘“The Epitheatrical Cartoonist”: Matthew Somerville Morgan and the World of Theatre, Art and Journalism in Victorian London’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 6. (2011), pp. 363-384 (p. 367). The first major exhibition shown at ‘The Gallery’, as it was known, included work by William Powell Frith, John Millais’s Ophelia (1851-2) and is, as Richard Scully describes, “chiefly remembered for showing [James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s] Symphony in White, No.1: The White Girl,”, following its rejection by the Royal Academy (Scully, p. 373) [back].

7 PNG files; a file size much smaller than that of the source TIFF [Tagged Image File Format] (Mussell, p. 98) [back].

8 Douglas Crimp, ‘Pictures’, October, 8 (Spring, 1979), pp. 75-88 (p. 75). [back].

9 See Tate’s ‘Art Term: Postmodernism’ https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/postmodernism> [accessed 18 October 2018] for more information [back].

10 Hito Steyerl, ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’, e-flux (November 2009) https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/ [accessed 16 October 2018] [back].

11 See Mussell, Nineteenth-Century Press in the Digital Age for a sustained engagement with the relationship between the twentieth-century digital resource and nineteenth-century print object. [back].

12 Steyerl [back].

13 Douglas Crimp, On the Museum's Ruins (Cambridge, Mass; London: MIT Press, 1993), p. 48 [back].

14 Crimp, p. 58 [back].

15 Julie Codell and Linda K. Hughes, ‘Introduction’, in Replication in the Long Nineteenth Century: Re-makings and Reproductions, ed. by Julie Codell and Linda K. Hughes (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018), pp. 1-20 (p. 10) [back].

16 Ibid, p. 14 [back].

17 Laric’s exhibition Kopienkritik (Copy Critique) at the Skulpturhalle in Basel in 2011 adopted a nineteenth-century methodological approach to ancient sculpture, which viewed (inferior) Roman “copies” in terms of (superior) Greek “originals”. Laric cast and grouped the museum’s collection of Greek and Roman plaster casts into typologies in order to reconstruct the lost originals via the “inferior” later copies. I am grateful to Dr Elizabeth Johnson for bringing Laric’s work to my attention. [back].

18 Frances Fowle, ‘Henry Walls: Chatterton (1856)’, Tate https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/wallis-chatterton-n01685 [accessed 16 October 2018]. [back].

19 Ibid [back].

20 Heroine of Trafalgar: The Fighting Temeraire’, National Gallery https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/learn-about-art/paintings-in-depth/heroine-of-trafalgar-the-fighting-temeraire [accessed 16 October 2018] [back].

21 Ibid [back].

22 'Skyfall', Wikiquote (9 August 2018) https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Skyfall [accessed 16 October 2018] [back].

23 For a summary, see 'Isabella, or the Pot of Basil', Wikipedia (28 November 2017) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isabella,_or_the_Pot_of_Basil [accessed 16 October 2018] [back].

24 E.B.S. ‘Eleanor F. Brickdale, Designer and Illustrator’, The Studio (London) 13 (1898), p. 106. Cited in George P. Landow, ‘Isabella and the Pot of Basil by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale’, The Victorian Web http://www.victorianweb.org/painting/brickdale/drawings/16.html [accessed 16 October 2018] [back].

25 Isabella and the Pot of Basil by Joseph Severn’, The Victorian Web http://www.victorianweb.org/painting/severn/isabella.html [accessed 16 October 2018] [back].

26 ‘About the artwork: The Scapegoat’, National Museums Liverpool http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/picture-of-month/displaypicture.aspx?id=379 [accessed 16 October 2018] [back].

27 Thomas Milton Kemnitz, ‘Matt Morgan of "Tomahawk" and English Cartooning, 1867-1870’, Victorian Studies, 19.1 (1975), 5-34 [back].

28 Gilda Williams, The Gothic (London: Whitechapel and The MIT Press, 2007), p. 14 [back].

29 Richard Scully, ‘Sex, Art and the Victorian Cartoonist: Matthew Somerville Morgan in Victorian Britain and America', International Journal of Comic Art, 13.1 (2011), 291-325 (p. 295) [back].

30 Ibid. p. 302 [back].

31 Ibid. p. 307 [back].

27 Jamie McKendrick, ‘Introduction’, in English Graphic, ed. by Marion Coutts (London: Frances Lincoln Limited, 2012), pp. 6-16 (p. 12) [back].